Food for thought

Aug 02, 2023

Five facts on farming, food and fossil fuels, inspired by Gates’ favorite author

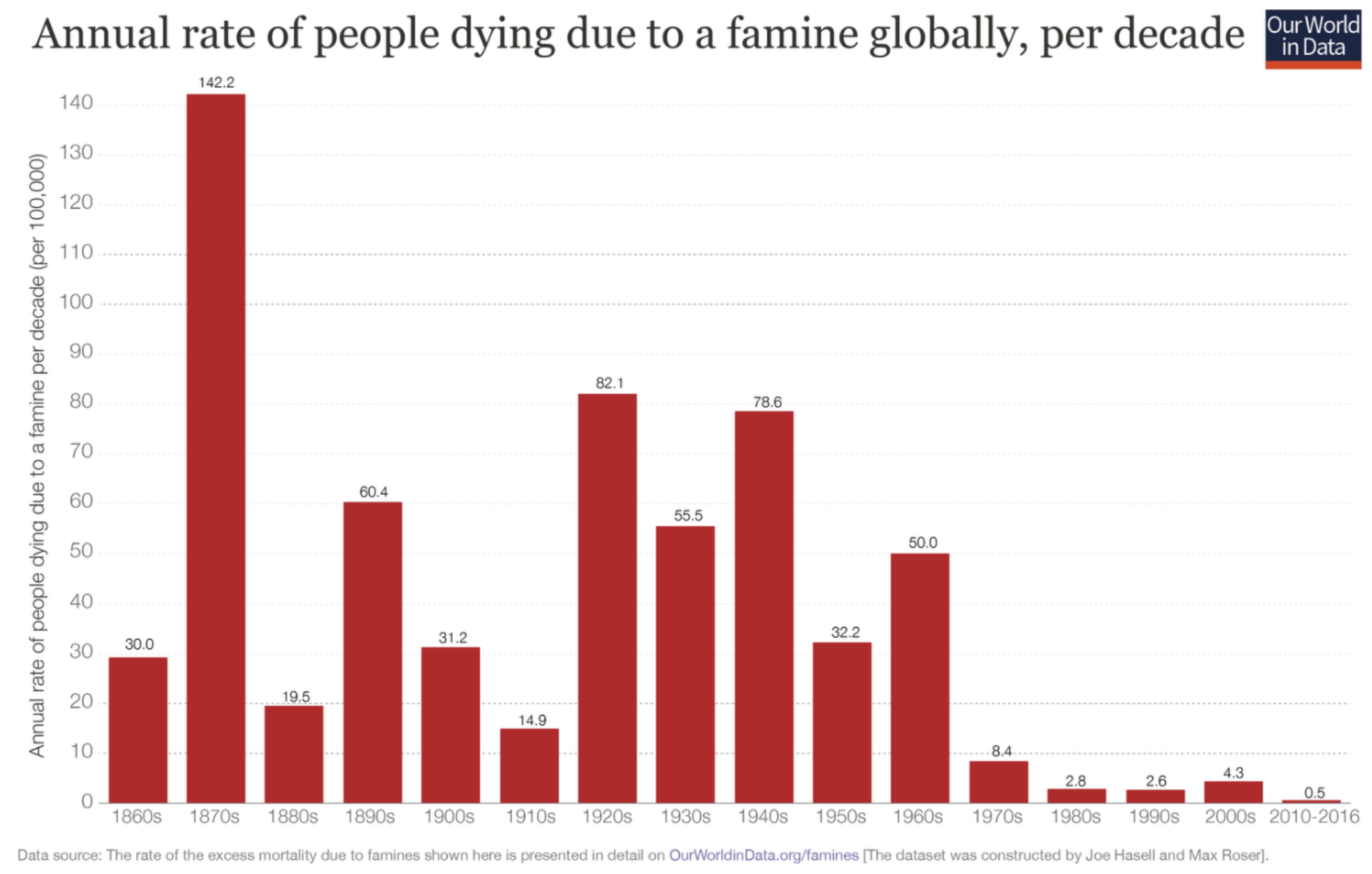

One – It is a miracle that we live in a famine-free world.

Famines were the norm. From the 1870s to 1970s, they claimed an average of nearly 1 million lives a year1. While malnutrition is a regrettable reality, famines have become rare and often avoidable.

In the last 50 years put together, famines claimed just 10% of lives of they used to previously take in a single year.

Having enough food is all the more impressive considering that over that time, the world’s population nearly has doubled from 4.4 billion in 19802. Add in the fact that we have been able to do this without increasing the land needed for agriculture, which has been flat worldwide since 19603, and you have a downright miracle.

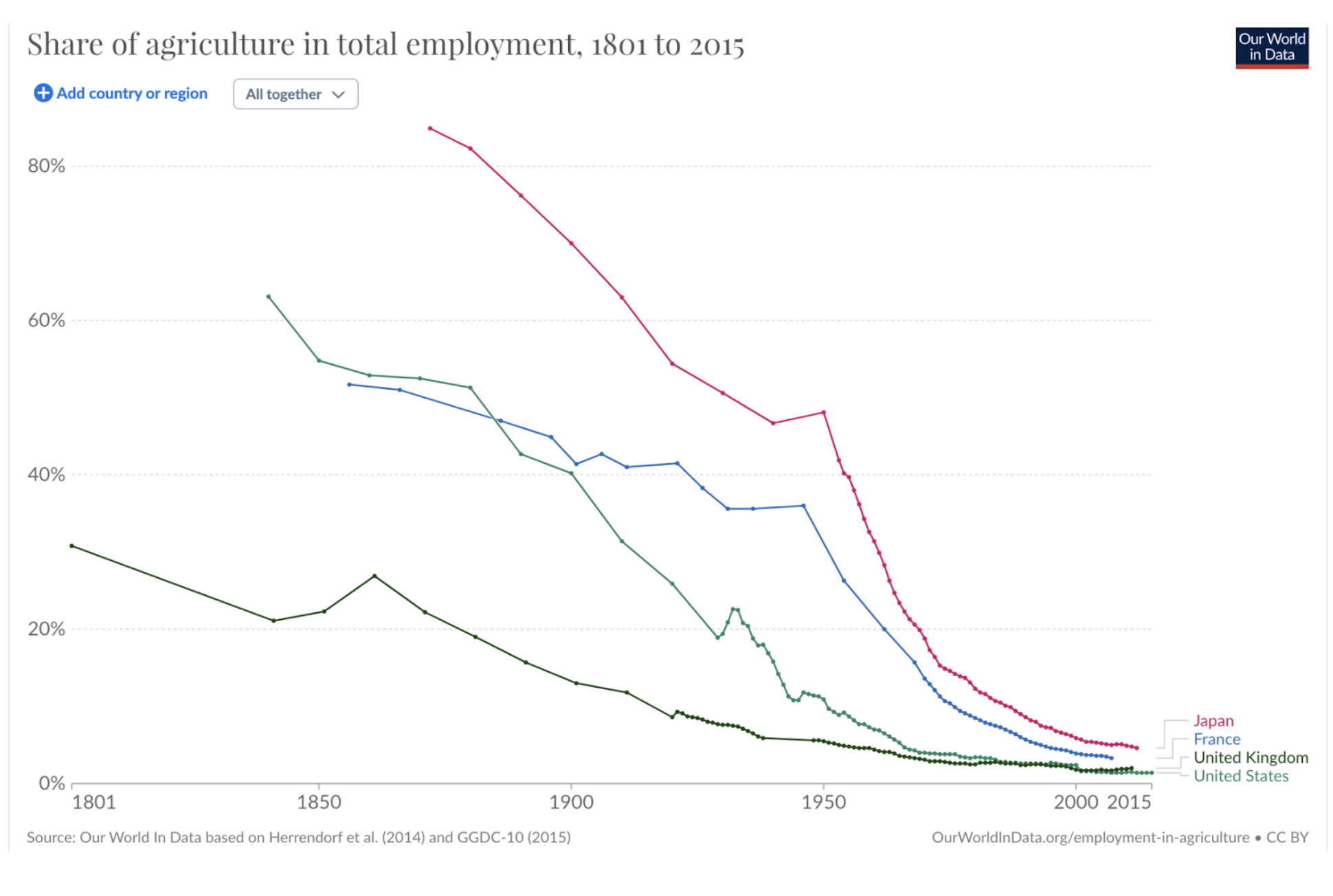

Two – This is a machine-made miracle.

Between 1800 and 2020, the share of America’s population engaged in agriculture dropped by a whopping 98%.

These downward trends, though sometimes less severe, hold across countries. How could this be possible if we’re growing more food than ever before? In How the World Really Works, Vaclav Smil shows that wheat production now requires less than two hours of human labor per hectare compared with 150 hours in 1800. This is made possible by mechanized steel plows to help plant seeds, large tractors to help maneuver them, and combines to help with harvest.

Fun fact #1: Before the advent of machinery and after the historic domestication of animals, there was at one point so much of a reliance on farm animals that at its peak, 25% of all farmland was dedicated to growing feed for them.

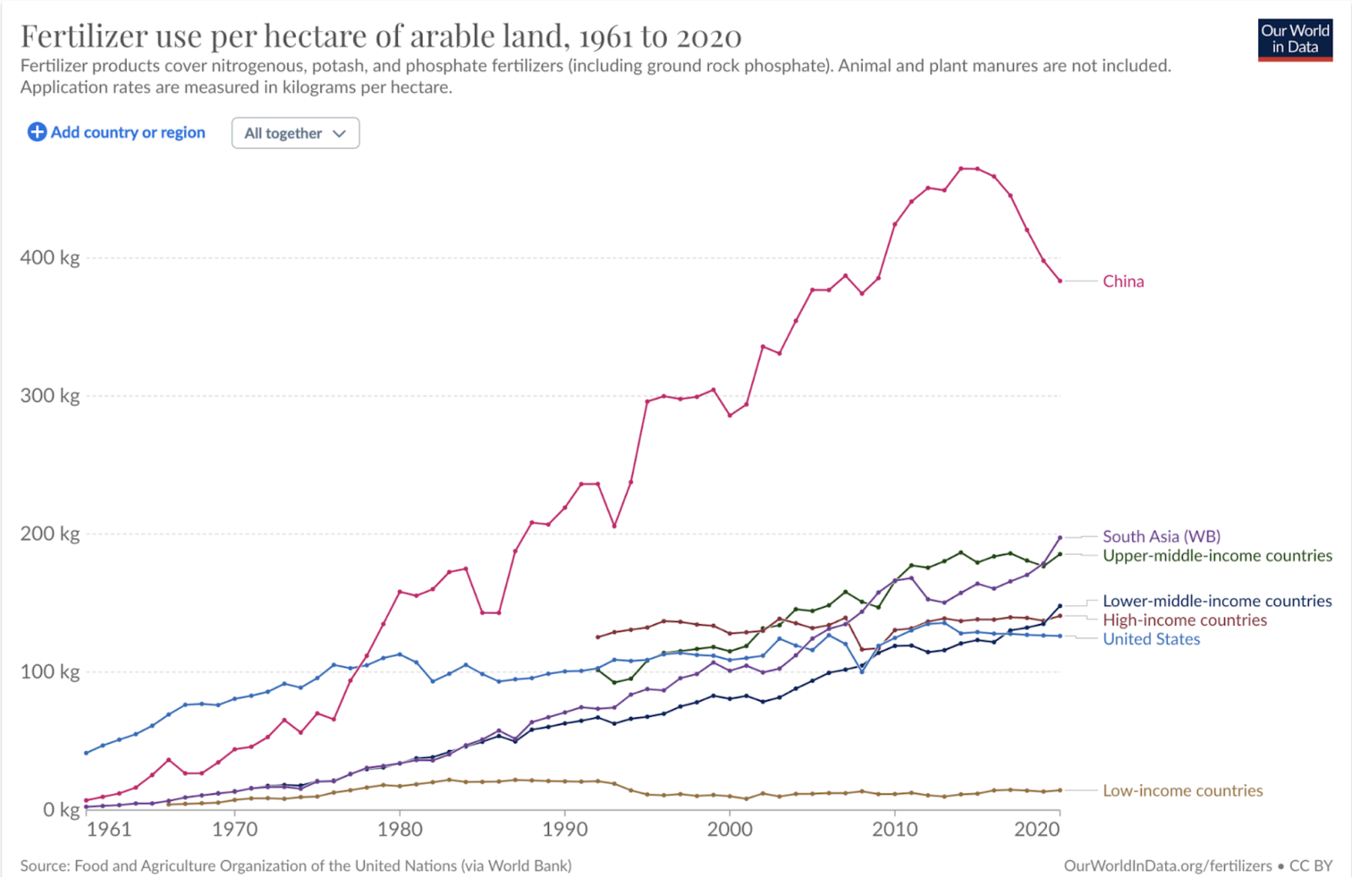

Three – The shitty reason our food is dependent on fossil fuels (it’s ammonia).

Just as crucial has been the use of ammonia to unlock high yield per unit farmland. High-yielding varieties of grain and most vegetables require from 100-200 kilograms of nitrogen (which along with phosphorus and potassium are the 3 plant macronutrients, just as proteins, carbohydrates and fats for humans). Traditionally, this came from manure, but given their low nitrogen content, it would take up to 10 to 30 tons per hectare to provide this nitrogen. Oh shit.

It takes an order of magnitude less of ammonia, and this efficiency, combined with our industrial abilities to manufacture ammonia through the Fritz-Haber process have made ammonia the source of 50% of all nitrogen needed to grow food.

Said differently, half of all the world’s food comes directly from our ability to synthesize ammonia.

The issue is, energy-intensive ammonia synthesis (powered by fossil-fuels today) is a leading cause of carbon emissions, leading to the same amount of emissions as all of South Africa4.

In addition, today, most farm machines, which are essential to producing the quantities of food necessary, rely on fuel for operation. Vitally, an immense amount of fossil fuel energy also goes into transporting and refrigerating the food we produce, accounting for 15% of global fossil fuel use.

Fun fact #2: China’s first major business deal with the US following President Nixon’s trip to Beijing in 1972 was to place an order of 13 cutting edge ammonia-urea plants from Texas.

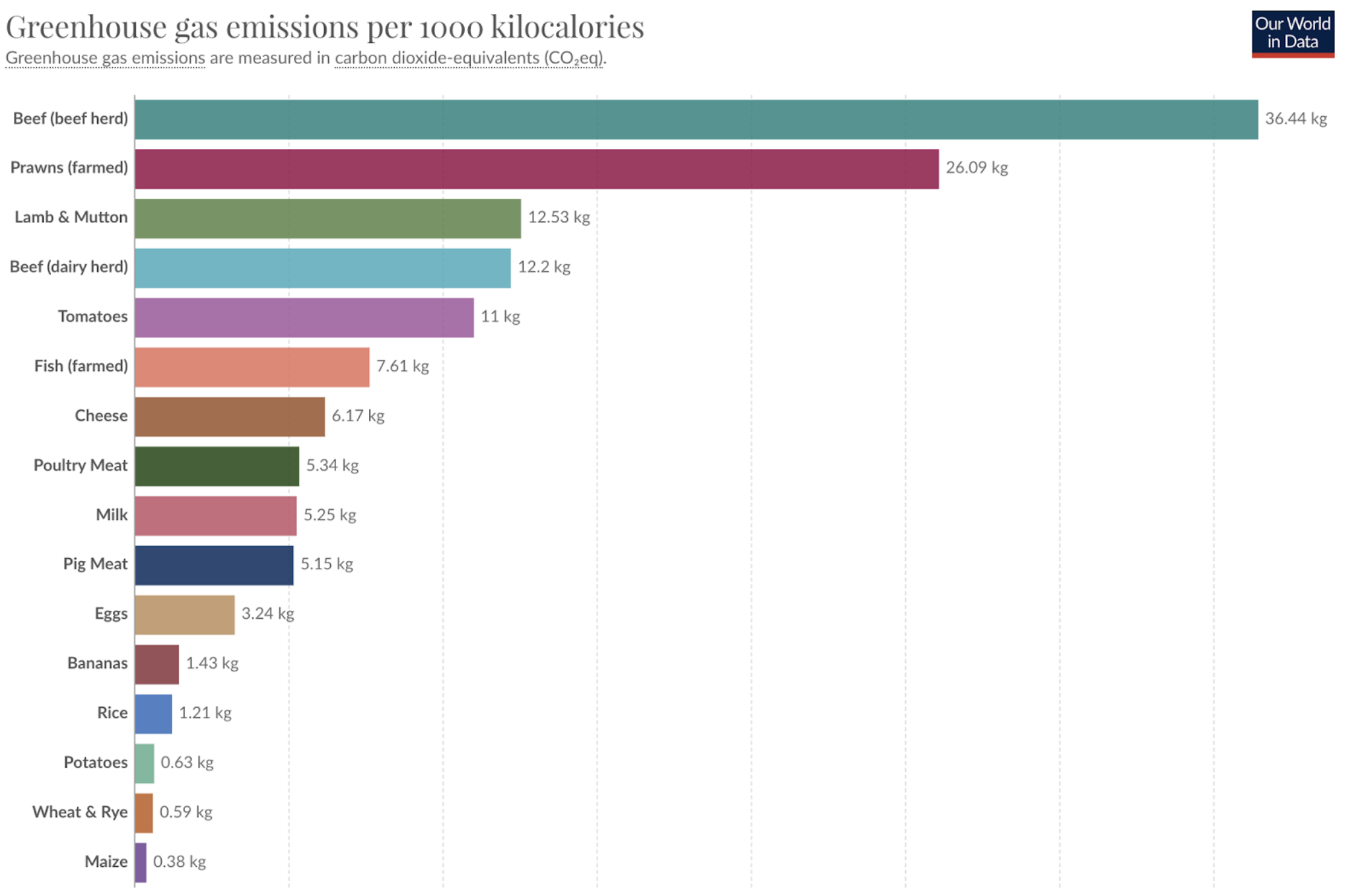

Four – Our conception of sustainable diets is broken.

In particular, a number of diets (organic, pescetarian, paleo) that have gained momentum in the media might not be having the positive impacts we implicitly expect. Given our reliance on ammonia (and machines), organic food is not as sustainable as you would think. In particular, if the nitrogen in your food isn’t coming from chemically synthesized ammonia, it’s likely coming from large amounts of animal dung (because it is a less efficient source of nitrogen for crops than synthetic ammonia). And those animals are likely being raised on ammonia-aided grain feed.

The environmental impact of pescatarian diets is even more fishy. A big reason for this is the diesel that is often necessary to power fishing boats and expeditions. Fisheries are not the answer either, since most fish that are grown this way consume other fish, which in turn need to be fished in boats. The overall impact of this is that consuming 1000 kcal of nutrition from fish requires an order of magnitude more energy than bread and 50% more than the maligned pork. Shrimp is nearly as bad as beef and open-water fishing is worse than aquaculture.

Vegan and vegetarian diets seem to be an exception, but with some asterisks. For example, tomatoes, which are often grown in warmed greenhouses and rely extensively on plastics, have twice the carbon footprint of nutritionally comparable chicken.

Beef and lamb are still incredibly carbon-costly, which means most paleo diets are categorically bad for the planet. But efficiencies in poultry-rearing mean that a paleo diet consisting purely of chicken is more efficient than a vegan diet that is tomato-heavy and reliant on imports. Vegetarian diets in the West don’t discriminate between when which fruits and vegetables are being eaten. Given that 15% of all food-related fossil fuel consumption comes from energy needed for shipping and storing foods, it is likely that many would be better off eating locally-grown chicken over imported avocados or mangoes.

Fun fact #3: Despite their enormous significance in Indian, Italian, Spanish and other cuisines, tomatoes are not endemic to them. They are native to Mexico and South America and were introduced worldwide by European transatlantic traders. A real fruit[^5] of early globalization.

Five – Food waste is tragic. It must be phased, not priced out.

If shopping organic from Whole Foods, going paleo or becoming vegan aren’t strictly correct answers to the food, and some meat seems essential for healthy eating – what can be done? We must waste less food.

Estimates from the Food and Agriculture Organization5 seem to suggest that nearly 30% of all food is wasted from harvest to consumption.

There is waste at every step of our complex food supply chains, and about half of all waste takes place until retail and half thereafter. Smil, in How the World Really Works writes that estimates from the UK’s Waste and Resources Action Programme show that almost 70% of wasted food is perfectly edible. In sum, wasting 20% of the world’s total food supply seems criminal. In addition to harvest and transport waste, there is also non-food waste in how crops are grown that is troubling. Estimates suggest that almost two-thirds of the nitrogen that is used to grow rice in China is not absorbed by plants6.

Economic incentives are good ways to limit waste, but food, like healthcare, has a peculiar distribution such that raising food prices might not work. Put simply, making food more expensive won’t eliminate waste by the rich, while making food significantly more expensive for the poor for whom food is already a significant portion of household incomes. We might have to fix food waste the old fashioned way: ordering less, finishing what we order and by keeping a closer eye on what’s in our fridges.

In sum, our relationship with food must change: too much of it is being consumed and wasted. It’s making us sicker and the world warmer. The average American consumes 100 kg (or 220+ lbs) of meat in carcass weight7. This is thrice the amount consumed in Japan, whose people also enjoy the longest lifespans.

Food’s future frontiers

Technology has facilitated both cultivating more land (thanks to mechanization) and increasing the yield per land (thanks to high-yield variety seeds, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides). But what’s remarkable is that how we grow – and consume – food hasn’t fundamentally changed dramatically for centuries. But this approach – of getting more out of the same – seems to have run out of road.

Changing the food landscape would require addressing some fundamental bottlenecks: supplying crops with nitrogen more effectively, synthesizing ammonia more greenly, or dramatically changing how meat is grown.

Advances in biotechnology8 might help crops fix their own nitrogen, limiting the need for ammonia. Meat is being successfully cultured in in labs, which could stall growing carbon emissions from rearing animals for food9. For all their promise, it remains to be seen if they can scale to satiate the world’s hunger. Indeed, feeding nearly 10 billion people thanks to expensive new technologies, at the prices of food from traditional farming, which matured over centuries, will be an uphill battle. Smil finds this incredulous. I don’t share his pessimism – after all, only 50 years ago, a world without famine seemed just as out of reach.

-

“Famine Trends Dataset, Tables and Graphs – World Peace Foundation”. sites.tufts.edu. 14 April 2017 Famine Trends Dataset, Tables and Graphs - World Peace Foundation link ↩

-

Executive Summary – Ammonia Technology Roadmap – Analysis - IEA link ↩

-

Food loss and waste – Nutrition (https://www.fao.org/nutrition/capacity-development/food-loss-and-waste/en/) ↩

-

Smil, Vaclav How The World Really Works, 2021 (page 73) ↩

-

Smil, Vaclav How The World Really Works, 2021 (page 73) ↩

-

Making real a biotechnology dream: nitrogen-fixing cereal crops – MIT News link ↩